The Amazon is the biggest continuous tropical forest on our planet. It has an important function as carbon reservoir (biomass carbon stored in its trees and soil) and carbon sink (taking up more CO2 than it releases). Both of these functions are however under continuous threat from human activities and climate change (Brienen et al., 2015).

In this work we analysed the changes in biomass carbon over the entire Amazon biome and investigated the amount attributed to different processes. These processes include deforestation, regrowth of secondary forests and forest degradation including edge effects. Degradation is the loss of a forest’s structure and function due to disturbance and is usually due to fires or selective logging, where high-value trees are removed from the forest. These processes combined with climatic pressures also lead to forests losing biomass close to newly created forest edges, which we call the “edge effect” (Silva Junior et al., 2020).

To monitor biomass over time (2011-2019), we used a new product of vegetation optical depth (VOD) which represents the amount of water stored within vegetation and is therefore closely correlated with its biomass. We also used high-resolution (30 m) satellite observations to track changes in land-cover and forest states, from intact to degraded, to model changes in biomass due to different processes.

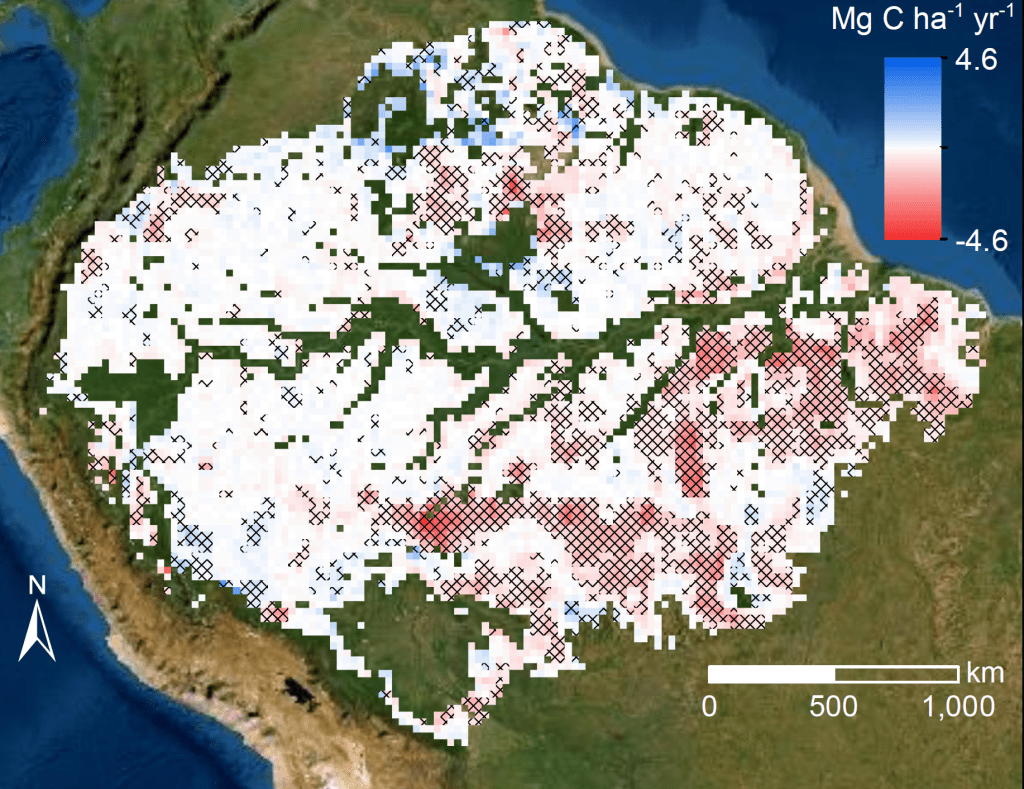

Fig. 1: Trends in aboveground biomass carbon (2011–2019) over the Amazon biome. Grid-cells where trends are significant are indicated with cross-hatches and cells where reliable data were not available are omitted (e.g. flooded areas and regional anomalies).

Changes in VOD over time revealed that areas of the Amazon forest losing significant amounts of biomass are about five times greater than areas gaining biomass (Fig. 1). Over 2012-2019 this resulted in a total reduction of ~1.3 petagram (1.3 * 1012 kilograms), a substantial amount despite the enormous size of the forest.

This is mostly explained by total deforestation increasing substantially since 2012 (Fig. 2b) due to changes in Brazil’s forest code. Indeed, Brazil (containing roughly two-thirds of the Amazon’s Carbon stocks) accounted for almost 80% of total biomass losses due to its larger-scale deforestation. Deforestation brings with it the creation of many new forest edges which subsequently lose biomass due to degradation processes (as seen by the simultaneous increase in Fig. 2a). Intact forests show variable behaviour with a slight decrease in biomass after an increase in 2011, indicating that overall mortality might exceed growth in recent years which demands further study.

Fig. 2: Time series showing (a) annual changes in AGC over the Amazon for 2011 up to 2018 as modelled for each process and (b) total AGC from 2011 to 2019 over the Amazon, modelled and inferred from VOD. Ribbons represent uncertainties associated with the data (see paper for more information).

The current data is still a bit too uncertain to infer the exact magnitude of year-to-year changes in intact forests whereas trends are more reliable. Because the VOD is sensitive to water content, it is also sensitive to water stress that isn’t necessarily linked to biomass change. Despite extensive data filtering procedures, this influence can’t be removed entirely. Further research using datasets from new satellite missions and updated forest plot measurements will help form a better consensus on the state of Amazon biomass.

Meanwhile, this study provides further evidence for the pressing need to reduce Amazon deforestation, particularly also due to its less visible but associated biomass reductions due to escaped fires and edge effects. There is hope that with the recent change of government in Brazil, the worrying trend in deforestation can be reverted and forests allowed to regrow to, in part, mitigate carbon emissions.