With drones being explored as a more proximal and flexible remote sensing tool, miniaturised multispectral cameras (Fig. 1) were quick to follow. The fine resolution spectral information that such systems can provide is exciting as we can monitor individual plant canopies and vegetation elements and it gives us a better idea of how this information scales to the coarse but global coverage of satellite data.

There are however multiple factors to consider when it comes to data from such systems. Data quality is influenced by the quality of the sensor itself, including dark noise and dynamic range properties of the sensor and distortions such as fisheye effects caused by the lens and vignetting. See Kelcey and Lucieer (2012) for an excellent description of these factors. The acquisition method and platform also play a role: For fixed mounted systems it’s impossible to ensure that the sensor is always pointing at nadir due to movement of the drone in flight. This can be partly rectified by angled mounting on multirotor systems anticipating the average tilt, but tilt, torque and turn will still vary throughout the flight if there’s any wind at all. Therefore, parallel flight lines may image the scene from slightly different angles, introducing so-called BRDF (bidirectional reflectance distribution factor) effects as most surfaces reflect light differently depending on the direction.

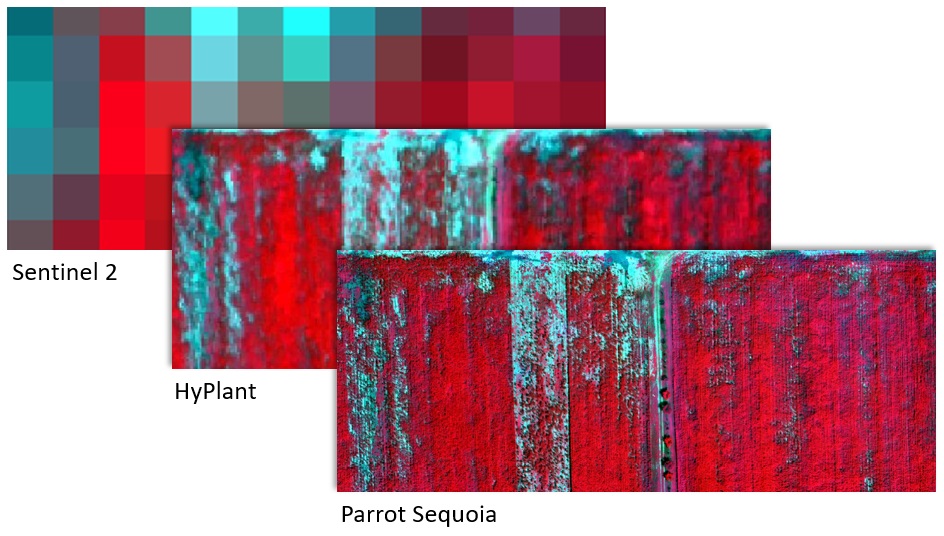

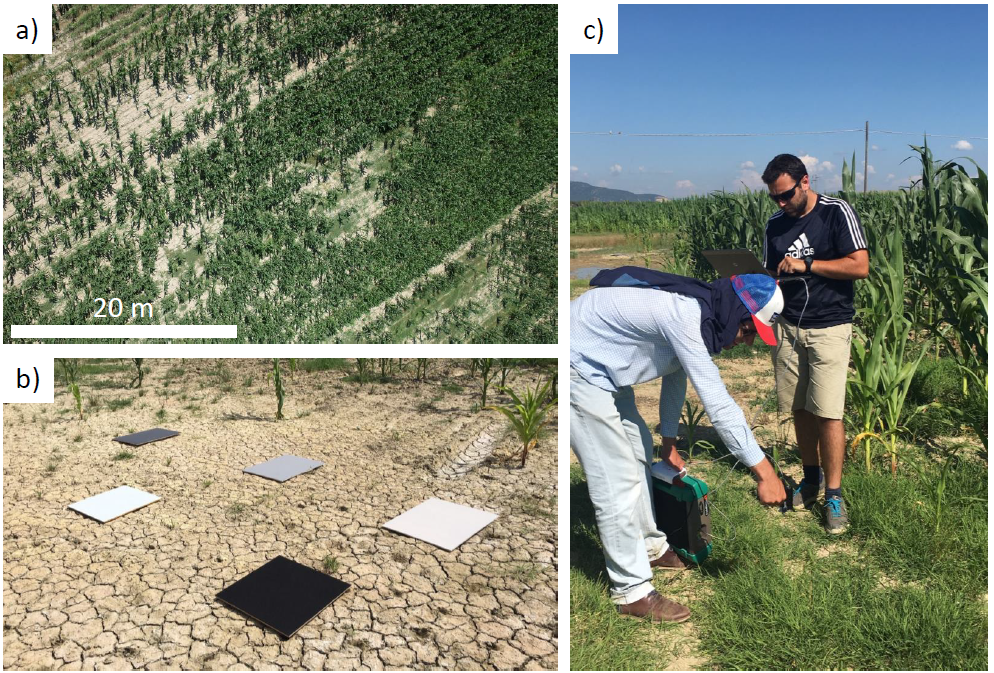

A field campaign which included overflights with the HyPlant hyperspectral instrument and same-day Sentinel 2 overpass (Fig. 2) gave us the perfect opportunity to assess the quality of drone based reflectance and vegetation index outputs. Such a comparison of reflectance maps to those from state-of-the-art and well calibrated instruments hadn’t been done before. At the same time we took spectral measurements over reference targets on the ground for additional validation (Fig. 3). This whole operation was very time-critical as the time between HyPlant acquisition, spectral measurements and drone flights needed to be as short as possible, all while dodging isolated clouds passing overhead and casting shadows on the surveyed maize field.

We showed that reflectance in drone products tended to be higher for dark surfaces and shadows, an offset observed in all bands. Conversely, areas with higher reflectance in the visible bands were slightly underestimated when compared against the HyPlant values. We anticipate that both dark current and adjacency effects had some influence on the drone measurements, particularly for the darker surfaces, but we weren’t able to untangle these influences in this work.

Assessed against reflectance panels deployed in the field (Fig. 3 b) and the HyPlant dataset we found errors in the 10% range which are acceptable for some applications but reveal the limits of this current generation of sensors for high quality reflectance estimations. However, calculating vegetation indices from reflectances can circumvent some of these biases and indeed they showed a strong relationship with indices derived from airborne and satellite measurements. Effects introduced by angular differences between flight lines were also smaller than expected. Combined, this demonstrates that vegetation information from drones has good potential to be used in workflows that integrate it with satellite data.