In this first published work from my PhD I surveyed an oil palm plantation using drone-based structure-from-motion. Simply put, structure-from-motion (SfM) is the methodology of deriving 3D point clouds from overlapping images by identifying the same tie-points in multiple images taken from slightly different angles. The “motion” refers to the fact that either the object imaged or usually the platform taking the pictures must move to provide these different perspectives. Coupling this with a method to assign real-world coordinates either to visible locations in the images (e.g. ground control markers) or of the platform that was acquiring the image, we can determine distances between points. For more information on concepts of digital photogrammetry, SfM and recommendations for its use in the geosciences, reading Chandler et al., 1999 and our update paper is a good place to start.

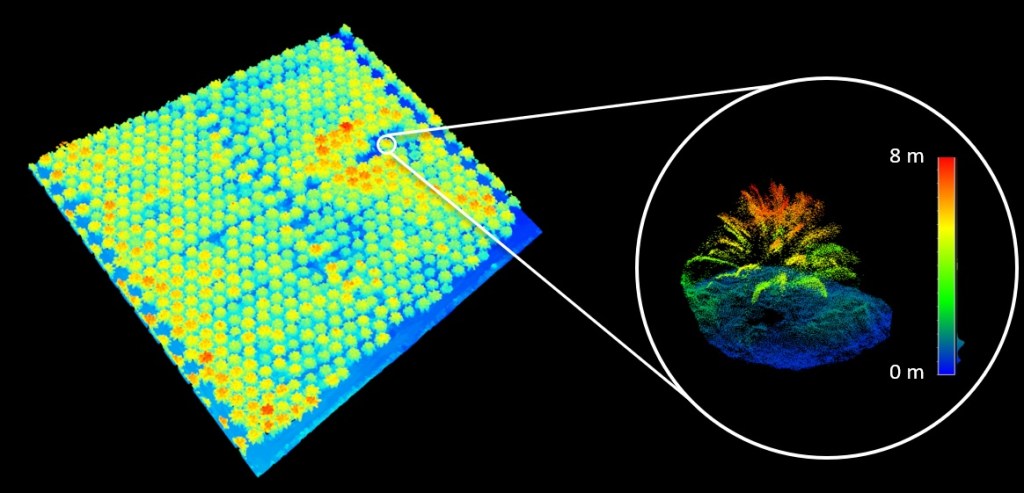

In this work we used SfM to identify and derive height metrics of individual oil palms in a plantation in Sarawak, Malaysia (Fig. 1). One of the challenging aspects of this work was that deriving vegetation height from SfM usually relies on knowing the elevation of the ground surface from a digital terrain model (DTM). Because there is relatively little terrain variation in plantations we were able to interpolate patches of ground visible from above, and thus captured in the SfM point cloud, to provide a DTM. Ground points were automatically identified using a morphological filtering procedure implemented in the excellent lidR package. We asserted the quality of this rudimentary DTM with GPS measurements in the field and it had an acceptable margin of error for our purpose (~10 cm).

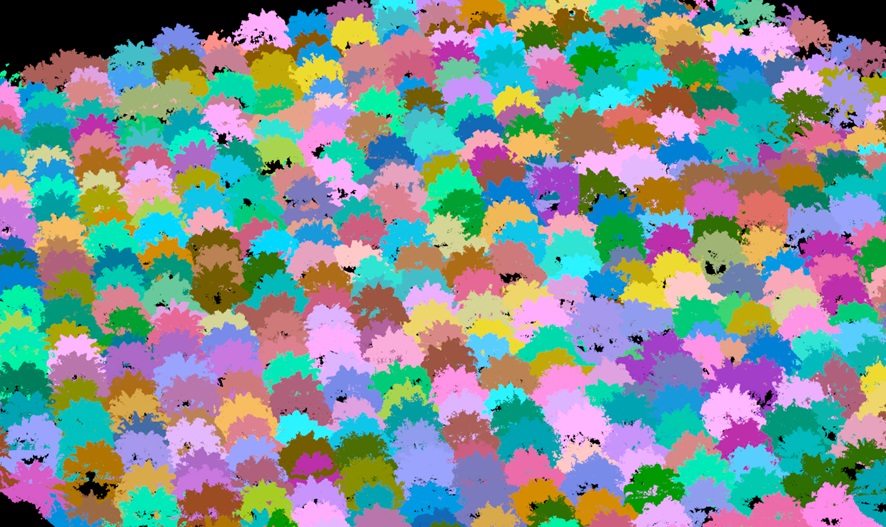

Palm identification based on local maxima with distance constraints and segmentation with variable radius based on height worked relatively well (Fig. 2), again a feature of the lidR package. We showed that segmentation becomes more difficult as soon as there are a substantial number of overlapping fronds from neighbouring palms, as was the case for a 10 year-old plantation. When palms are too small (2 year-old) compared to surrounding vegetation and man-made features, such as piled up dead wood between plantation rows, this introduces another challenge. For a 7-year old plantation, neither of these issues were present so the approach worked best (98% of palms identified).

While computer vision methods may perform similarly or better for palm identification, the novelty and advantage of the SfM approach is that the height metrics we can calculate from the point clouds are closely linked to the palm’s biomass and therefore could provide a convenient way to estimate carbon stocks of entire plantation blocks. Such estimates are important for quantifying the impact of forest clearing and plantation establishment on the carbon budget, though the fate of the biomass post-clearing of old, less-productive plantations after 25-30 years is a critical part of this equation.