Airborne hyperspectral measurements are used to derive the reflective properties of the land-surface from the visible to the near-infrared light and beyond. For vegetation, these reflective properties can be used to gain information on its structure and health.

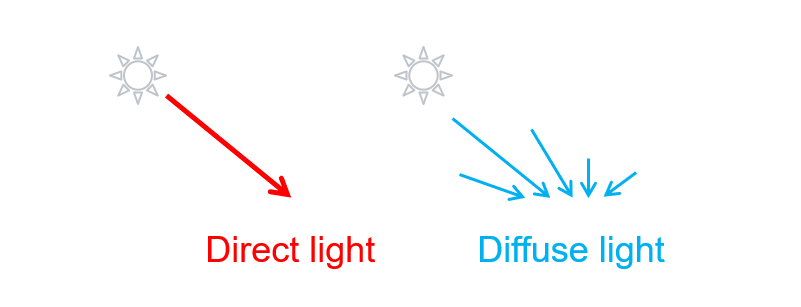

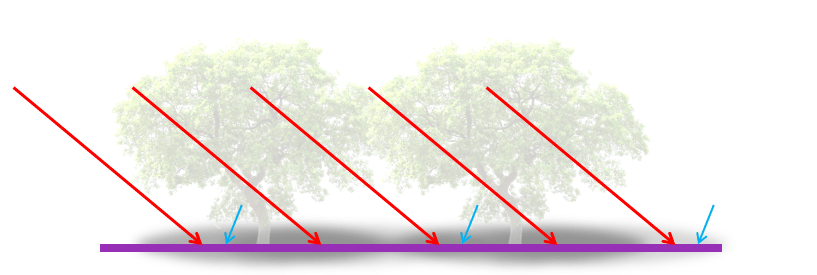

To calculate reflectance from measurements of reflected light (radiance), we need to know the corresponding irradiance at that location (pixel). Usually, this is estimated by combining the direct irradiance (light from the direction of the sun) and the diffuse irradiance (light from all directions that has been scattered in the atmosphere, Fig. 1) that would reach a flat or simplified earth surface (Fig. 2). Because the landscape is complex and covered by trees that have different crown shapes and cast shadows, these irradiance estimates are not accurate. Errors in irradiance result in errors in reflectance and finally in the quantities derived from reflectance like metrics of vegetation health including chlorophyll content.

In this work, we proposed two physically based methods to improve irradiance estimation and investigated their impacts on reflectance and selected vegetation indices.

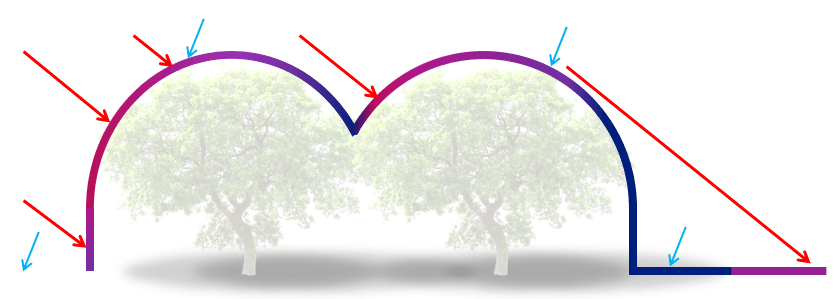

The first method (Fig. 3), relied on a digital surface model to represent the shape of trees (2.5 dimensional) and calculated irradiance at each point of the landscape based on this. Trees casting shadows block direct irradiance and therefore shaded areas will only be illuminated by diffuse irradiance.

The second method (Fig. 4) used voxel (3D pixels) based representations of trees where voxels have different properties including the density of leaves. The main difference to the first approach was that this method could simulate some direct light passing through the tree crown as well as light being scattered between leaves, all of which influence the amount of light at different wavelengths reaching the shaded areas.

An example of our results is shown in as an RGB image based on reflectance data from a section of the studied landscape (Fig. 5). A) shows the standard approach without any adjustments (no representation of trees for irradiance calculation), B) shows the results from method one (Fig. 3) and C) shows the results from method two (Fig. 4).

If the methods worked perfectly, we’d expect to see an image that looks like A) with all shadows removed. We can see in B) and C) that larger cast-shadow areas do look closer to their expected true values, however there are also regions with implausible values, particularly in the fringes of these shadows. This is expected as the data used to represent tree shapes doesn’t match exactly with reality. Nevertheless, some vegetation indices derived from this data improved considerably, indicating that there’s some value to these approaches. We suggest for example, that these physically based methods could be used to generate reference values to be combined with an automated shadow detection routine, similar to the one presented in Schläpfer et al. (2017).